I’ve heard the internet say that Daria indoctrinated a generation of eccentric, tween girls into the cult of man-hating slackerdom. But personal experience tells me that Daria did not exploit my teen angst to implant a subversive worldview—she unearthed the sardonic feminist lying dormant within, quietly anticipating the upheaval of adolescence to make herself known.

Origins

Many modern works of fiction whether poignant, cultural commentary or cringey, G-rated cow dung, begin as capitalistic endeavors and Daria, MTV’s spin-off of Beavis and Butt-head, was no different. As co-creator Susie Lewis recalled in a 2024 interview with Twelve Snakes, talks of the series began in ’96, when MTV’s animation department was taking off, and executives wanted to cash in on a “Beavis and Butt-Head for girls.”

But what started as a metaphorical Pied Piper, luring alternative girls to a consumerist playground of Walkmans and combat boots, evolved into a satirical critique of capitalist conditioning in public schools, a cutting-edge portrait of adolescent life in existentially bankrupt suburbia, and, most importantly, an exploration of intimate female friendship that renounced boy worship for a shared point of view and an undying love for pizza.

Episode 1: The Esteemsters

Welcome to Lawndale

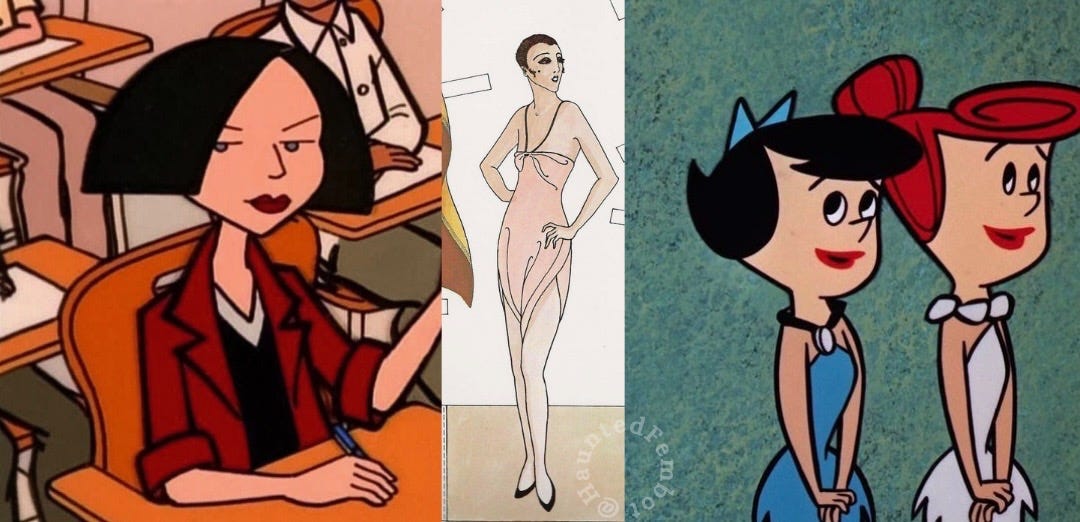

“The Esteemsters” begins in a moving car, a visual cue that this story is taking Daria and her audience away from the crude world of Beavis and Butt-Head and into something sharper, something more refined. Daria is no longer a squiggly, half-baked sidekick. She is the fully realized, illegitimate love child of Velma Dinkley and Janeane Garofalo, here to rebrand girl geeks as riot grrrl rebels.

We learn that Daria and her family have left Highland, Texas for Lawndale, an affluent mid-Atlantic suburb in an unnamed state. As Jake, Daria’s emotionally intense father, offers a pep talk about making new friends, Daria cracks wise in the backseat, “speak up, Dad,” she quips as she turns up the volume on the radio.

Meanwhile, her younger sister, Quinn—an animated Cher Horowitz in a pink baby tee—primps in anticipation of the unpopulars who will worship at the altar of her charm.

As soon as the car stops, Quinn is swarmed by adoring fans she hasn't even met yet: “cool shirt,” “cool name,” “will you go out with me?”— they coo as she flips her hair and giggles.

Daria, emerging from the car like an afterthought, promises her dad to help Quinn through this difficult period of adjustment.

The Lawndale Industrial Complex: Where Individuality Goes to Die

Inside the walls of Lawndale High, we experience the condescension and “whistle while you work” capitalist grooming that American public high schools are designed to impose. Principal Angela Li—authoritarian, image-obsessed, and corporate to the bone—welcomes a gaggle of new students with the forced enthusiasm of someone who knows optics are everything. To no one’s surprise, Lawndale High’s “warm welcome” comes with a mandatory psychological evaluation designed to weed out students with subversive attitudes. Certainly, this is a tool for self-improvement, not an ideological sorting mechanism.

Echoing a pivotal scene from 1976’s Carrie, in which the school principal meets with Carrie to discuss her radically disruptive behavior, then dismissively and repeatedly refers to her as “Cassie,” the Lawndale school psychologist, Mrs. Manson, continually addresses Daria as “Dara.” Signaling a subversion of the original story in which Daria, like the cruelly alienated Carrie, unleashes a fatal attack on the system that underestimated her, this scene lets us know that Daria will not be tolerating transparent attempts to intimidate or control her.

Holding up an illustration of two people talking, Mrs Manson instructs the girls to describe what they see. Quinn, a born politician, understands that the system exists to be manipulated, and responds with the banalities expected of a typical teenage girl. Daria, on the other hand, offers up a patronizing pageant response about puppies, to which Mrs. Manson scoffs in frustration.

Later, in history class, we are introduced to Mr. DeMartino, a hostile scream of a human being who must share DNA with Charlie Sheen.

He introduces Daria to the class, his caffeine- fueled eyeball rattling crudely in its socket, and immediately quizzes her:

Mr. DeMartino: "Daria! Can you concisely and unemotionally sum up for us the doctrine of Manifest Destiny?"

Daria: "Manifest Destiny was a slogan popular in the 1840s. It was used by people who claimed it was God's will for the U.S. to expand all the way to the Pacific Ocean. These people did not include many Mexicans."

When his reach for intellectual superiority leaves him empty-handed, he moves onto school quarterback, Kevin Thompson, who supposes that Manifest Destiny was part of Operation Watergate during the Vietnam War.

Show a Little Trust

At home, the dinner conversation turns to the first day of school. It seems that while Daria spent the day incurring the bitterness of every school authority at Lawndale High, Quinn accepted an official position as the vice president of the fashion club. She's also considering joining the pep squad, but she’s not sure it will fit into her schedule.

As the family pokes at their lasagna, Helen, Daria’s high-strung, career-driven mother, learns that Daria has been enrolled in a mandatory self-esteem course at school. Daria insists that she does not have low self-esteem, but in fact has low esteem for everyone else.

Still, Helen urges her to "show a little trust" and "maybe make a friend."

Enter Jane Lane: The Artful Dodger

Self-esteem class is taught by Mr. O’Neill, a sentient pink button-up with the depth of an emotional-support goldfish. He delivers his opening speech like a New Age self-help tape left out in the sun: "Esteem a teen. They don’t really rhyme, do they? ...we are here to begin realizing your actuality…"

Growing increasingly frustrated with his hollow sentiments, Daria interjects: “I want to know what realizing your actuality means."

From behind, a sly, gravely voice whispers in her ear,“he doesn’t know what it means. He’s got the speech memorized. Just enjoy the nice man’s voice”

This is our introduction to the show's second protagonist, Jane Lane—a vampy Betty Rubble reimagined as a grunge-era, Erté paper doll. A glance at her asymmetrical DIY bob, deep red lipstick, and punk rock ear cuffs tells us that she the ultimate role-model for teen girls of a certain ilk. She is playfully cynical, artistic, and exquisitely suited to compliment our coldly rebellious, no-nonsense Daria.

The two walk home together, their easy camaraderie already established. Jane reveals that she is a seasoned veteran of the school’s attempts to rein in individualism. To date, she has endured Mr. O'Neill's course 6 times and knows it like the back of her two-dimensional hand.

"If you know all the answers, why don’t you just graduate?" Daria asks.

"I like having low self-esteem. It makes me feel special," Jane replies.

And just like that Enid has found her Rebecca, Angela has found her Rayanne, Butt-head has found his Beavis. And we have found our Jane Lane.

Later, at Jane’s house, the two watch Sick, Sad World, a tv program dedicated to documenting society’s most grotesque and ridiculous stories. This pastime will reoccur in nearly every episode of the show, positioning human stupidity as theater for the pair to mock from a comfortable distance.

Directly echoing Helen’s earlier advice about trust, Daria suggests that she and Jane graduate from self-esteem class together. The next day, they approach Mr. O’Neill and ask to take the final test early. Any skepticism he expresses is stilled when they effortlessly parrot the meaningless platitudes he has drilled into them over the last week:

"Self-esteem is important because it will stand us in good stead the rest of our lives."

"The next time I start to feel bad about myself, I’ll look in the mirror and say, 'You are special. No one else is like you.'"

"There's no such thing as the right weight or the right height. There’s only what’s right for me. Because me is who I am."

O’Neill, moved by his own empty cliches, declares that the whole school needs to see this miracle and schedules a Self-Esteem Class graduation assembly.

At the assembly, Daria and Jane stand up in front of their classmates to share an account of their experience. Jane approaches the mic, playfully glances back at Daria, and feigns a mental meltdown to make her laugh. Daria, following Jane’s lead, gives a saccharine speech bordering on parody, in which she names her sister Quinn a primary source of emotional support in her journey to find self-love. Quinn, having spent days convincing her classmates that she has no relation to Daria, shrinks in her seat mortified as Daria’s deadpan expression stretches into a cunning grin.

We end the episode at a science fiction convention where Daria has taken her family to revisit "the circumstances that brought her happiness as a child" (a recommendation from Mr. O'Neill). She is no longer enduring idiots from the backseat of a car; she is orchestrating their humiliation for her own amusement.

By the final scene, Daria has established herself as the voice of sarcasm in a world gone stupid; public school is offered up as a microcosm for middle-class american delusion and resentment; an all-you-can-eat buffet of nuanced characters serves complex exemplars of traditional and alternative femininity, and the heart of the show is set firmly in the budding friendship between Daria and Jane.

la, la, la, la, la.

Join me next time for Episode 2: The Invitation.

Become a paid subscriber to access original music track listings for every episode, full episode transcripts, videos, extended commentary, and archival Daria articles from 1997.

Very excited for this!